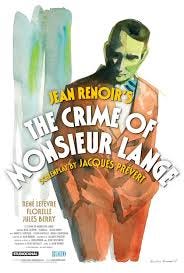

1935, the year the Swing Era officially kicked off in America with the popular acceptance of the Benny Goodman big band, was none too shabby a time in our country, culturally speaking. The same could be said of France. I’m reminded of this artistic high-water mark by way of watching The Crime of Monsieur Lange, one of a series of cinematic masterworks that director Jean Renoir made in the 1930s. I hadn’t seen Lange in decades, and when it showed up on the Criterion Channel, I pounced. (Released in January of 1936, Lange was produced the previous year. In discussing the film I adhere to the same rule that I would a jazz recording: the year (or years) it was actually made is the official “birth” date.)

What a gem this compact (77 minutes) film is! At the height of his considerable powers, Renoir displays the lightest of touches mapping the social, professional, romantic, and imaginative worlds — and, by extension, the political leanings — of the inhabitants of a small Parisian apartment building. Apart from a few scenes that take place elsewhere, the majority of the action occurs within rooms that dot the building’s courtyard. Undercut by a current of treachery and deceit, Lange oscillates between a heady atmosphere of Gallic whimsy and optimistic communality set against darker spirits. In lovely moments it can also seem like a mini-musical, with characters bursting into song as the mood strikes them. (It’s a French thing — joie de vivre and all that, I guess.)

The acting has a casual manner befitting the film’s loose texture. With one glorious exception, that is. Jules Berry gives a thrilling performance as the villain you love to hate. Berry’s admixture of seductive charm and nonchalant aggression fuels the film. We instinctively root for the little people that Renoir so obviously loves, the ones whose modest dreams stoke our sympathy. Yet Renoir is also nourished by the dramatic energy that Berry’s nefarious character churns up.

Renoir’s brilliant use of camera movement and deep focus shots lend the film a bravura technical élan that always enhances the narrative structure. Renoir makes sure to cloak his cinematic gifts within the ambiance of a scene; sparkle for its own sake is anathema to him. (On multiple viewings, and this is a film that richly deserves them, watch for the interior shot that features a “mistake” that my eagle-eyed daughter caught on her initial screening. There’s Renoir himself, reflected in a mirror, directing the scene. Accidents happen, even to geniuses.)

The Crime of Monsieur Lange may not have the scope of The Rules of the Game, but its compelling balance of delight and malevolence lingers as effectively as Renoir’s later masterpiece. Arizona Jim rules!

Maybe it was the calm before the storm — Nazis would be marching the streets of the city within five years — but Paris in 1935 brimmed with artistic creativity. The union of the Belgian Gypsy guitarist Django Reinhardt and the French violinist Stéphane Grappelli was still fresh when these virtuosos recorded “Djangology,” an outright celebration of both the guitarist’s shockingly adroit playing and the superb hookup that he achieved with his sophisticated partner. If Django reminds me of anyone it’s Jimi Hendrix. Both guitarists seemed to have this otherworldly musicality that was utterly inimitable — How did they fuse all their obvious influences into an unmistakably individual style so quickly? It remains a beautiful mystery.

Although I came of age entranced by guitar virtuosity, there are few things I now find more empty. Not only is Django’s work an exception to the rule, I find he transcends the title “guitarist.” Like Miles Davis on trumpet, Django completely exceeds the boundaries of his instrument, transforming the acoustic six-string into a separate tool, one expressly used to produce gloriously personal music. Listen to his sly playing on “Djangology.” The first chorus establishes his jaunty phrasing, beautiful tone, and relaxed swing. He waits for the second chorus to knock you off your feet. But hear how he then keeps pulling back, using his ridiculous technical gifts sparingly. He had what far too many guitarists who followed him lacked — intuitive artistry. Technique, he realized, is a gift to be offered with restraint, it’s not a magic trick to be flagrantly misused.

Grappelli was also a stunning player, a lyrical and swinging violinist when swinging violinists in Europe were a rare commodity. But there was only one Django.

I'll never forget the first time I saw M. LANGE. It left such an impression on me.

Elaine May was called in to advise on possible recutting of SWING SHIFT, and she coined a turn of phrase that stuck with me: "Why would you want to disturb the ecology of Jonathan's movie?"

The ecology of M. LANGE is so abundant and colorful and verdant, like a mountain meadow. What a thing of beauty. The same can be said of so many Reinhardt recordings.

As an aside, I've always loved the album that Stéphane Grappelli did with Gary Burton, PARIS ENCOUNTER. Especially the opening track, "Daphne."

Music AND movies! Nice. Django makes me think of the Woody Allen movie Sweet and Lowdown where Sean Penn is so funny saying he's the world's greatest guitarist...well, except for this guy in France named Django Reinhardt. Makes me laugh every time.