My friend Dave, on discussing Jimi Hendrix, has said that if they ever determine that the sublime guitarist was indeed an extraterrestrial, he wouldn’t be surprised. I tend to agree with him. Hendrix didn’t play his instrument like any other earthling, nor did he think about sonics itself as others did. He’s been gone for fifty-four years and yet his music still startles with unsurpassed audacity and imagination.

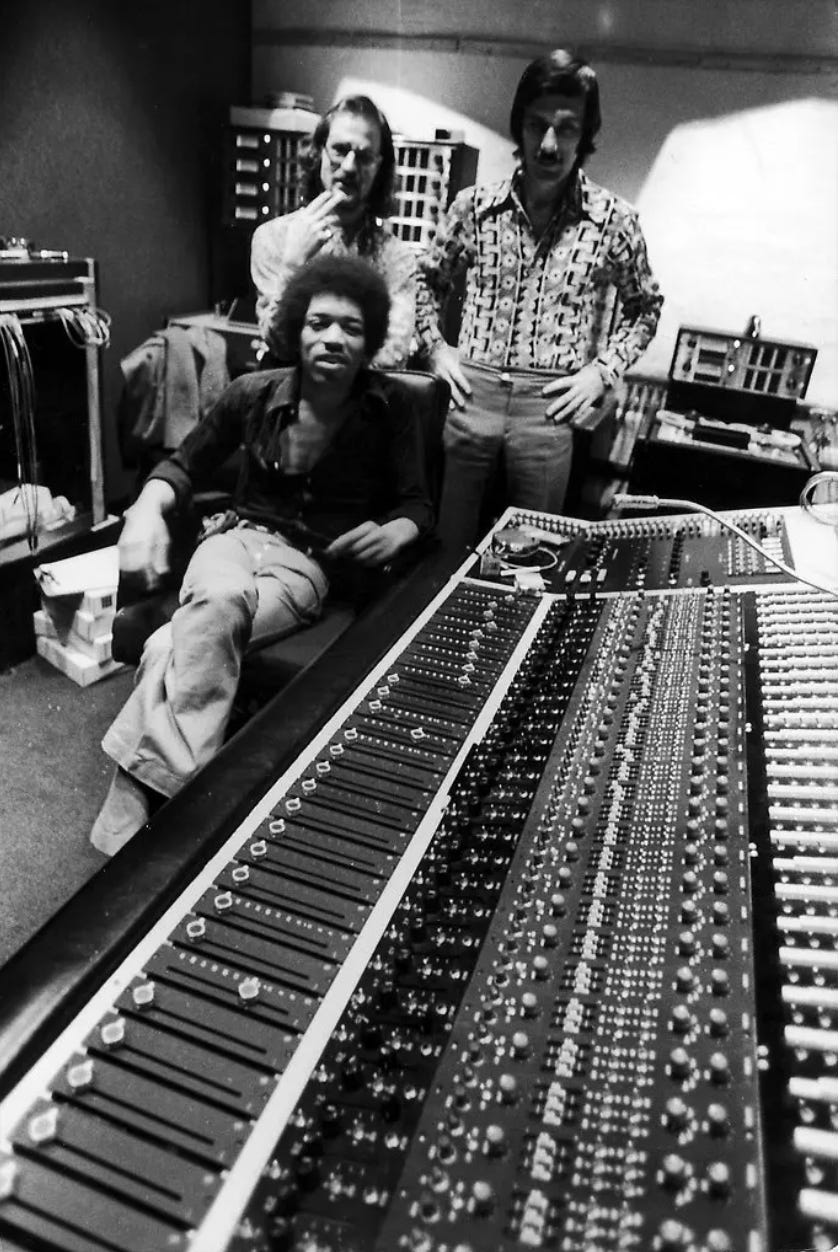

Recently, I spent an afternoon listening to the three-CD set Electric Lady Studios: A Jimi Hendrix Vision which contains 38 previously unreleased tracks that Hendrix cut at the recording studio he conceived and financed in New York City. (It’s still there, nestled within the commerce-intense environs of West Eighth Street in Greenwich Village.) Unfortunately Hendrix didn’t get to enjoy his dream project all that much. Within three months of the Electric Lady opening, Hendrix met his untimely end. But he seems to have taken advantage of his new toy, incessantly jamming and recording tracks for upcoming projects. Electric Lady Studios doesn’t capture it all, but there’s still plenty here, admittedly much more than the casual Hendrix listener might be willing to absorb.

But Electric Lady Studio wasn’t conceived for the casual Hendrix listener. There’s multiple takes of songs, long jams, incomplete performances. In other words, for a Hendrix fanatic, it’s bliss. The full afternoon I spent taking it all in may not have gone by in a flash, but every moment was worth attending to. Yet I’m also glad I culled a selected playlist from the massive trove — I’m not sure I’m hurrying back to hear Electric Lady Studio in its entirety anytime soon.

My takeaways? Hendrix, in the last few months of his life, was at the peak of his powers, both as a guitarist and, as the album title asserts, a studio visionary. Hear him on workouts like “Hear My Train a Comin’,” where he takes a traditional blues and transports it into, yes, outer space, or “Hey Baby (New Ring Sun),” an atmospheric dreamscape that seems plucked from the higher reaches of the atmosphere itself, and consider how his daring and passion sets him apart from all other electric guitarists of the rock era.

Songwriting was another story though. As exciting as such tracks as “Freedom,” “Dolly Dagger,” and “In From the Storm” are, Hendrix’s reliance on blues forms to build his newer compositions comes off as repetitive and confining. I kept imagining what it would have been like for Hendrix to have collaborated with songwriters who might have opened his harmonic and compositional imagination, say, Curtis Mayfield, Norman Whitfield, or, dare I even suggest, Stevie Wonder. Yet if his songwriting was inconsistent, tracks like “Drifting” and “Angel” — two of his greatest performances — exhibit new growth as a composer of dreamy and haunting ballads.

What Electric Lady Studio exhibits in bulk is Hendrix as an arranger of genius. Utilizing the studio as if it were an additional instrument, Hendrix multitracked guitar parts atop each of other with orchestral deftness and heft, brimming with sonic audacity. “Night Bird Flying,”“Freedom,” “In From the Storm,” “Room Full of Mirrors” and others become guitar-infused epics in his hands, the studio allowing him to turn his vivid imaginings real. These are gorgeous creations that are essential cornerstones of Hendrix’s legacy.

And can we have a hand please for Billy Cox, whose bass playing is so self effacing yet so consistently right. What a strange career: he meets and plays with Hendrix in the early Sixties when both were in the service. Having vowed to work with him again, Hendrix brings Cox back into the fold after he becomes a superstar. Replacing Noel Redding in 1969, Cox goes on to play Woodstock with his old buddy and then with the short-lived but transformative Band of Gypsies. A member of Hendrix’s last trio, where he joined the drummer Mitch Mitchell, Cox acquits himself with distinction throughout 1970. Hendrix dies that September. Cox, then not yet thirty, never joins forces with another major musical figure or participates in any significant recording again.

Though when you think about it, where could he have gone next? He had just made unforgettable music with a Martian.

Sweet piece, Steve. It really is captivating yet tough to imagine what it must have been like in his own studio, playing the whole damn place as his instrument. As you know I used to run into Hendrix very frequently in Chicago—in plaster form. Talk about unforgettable!!